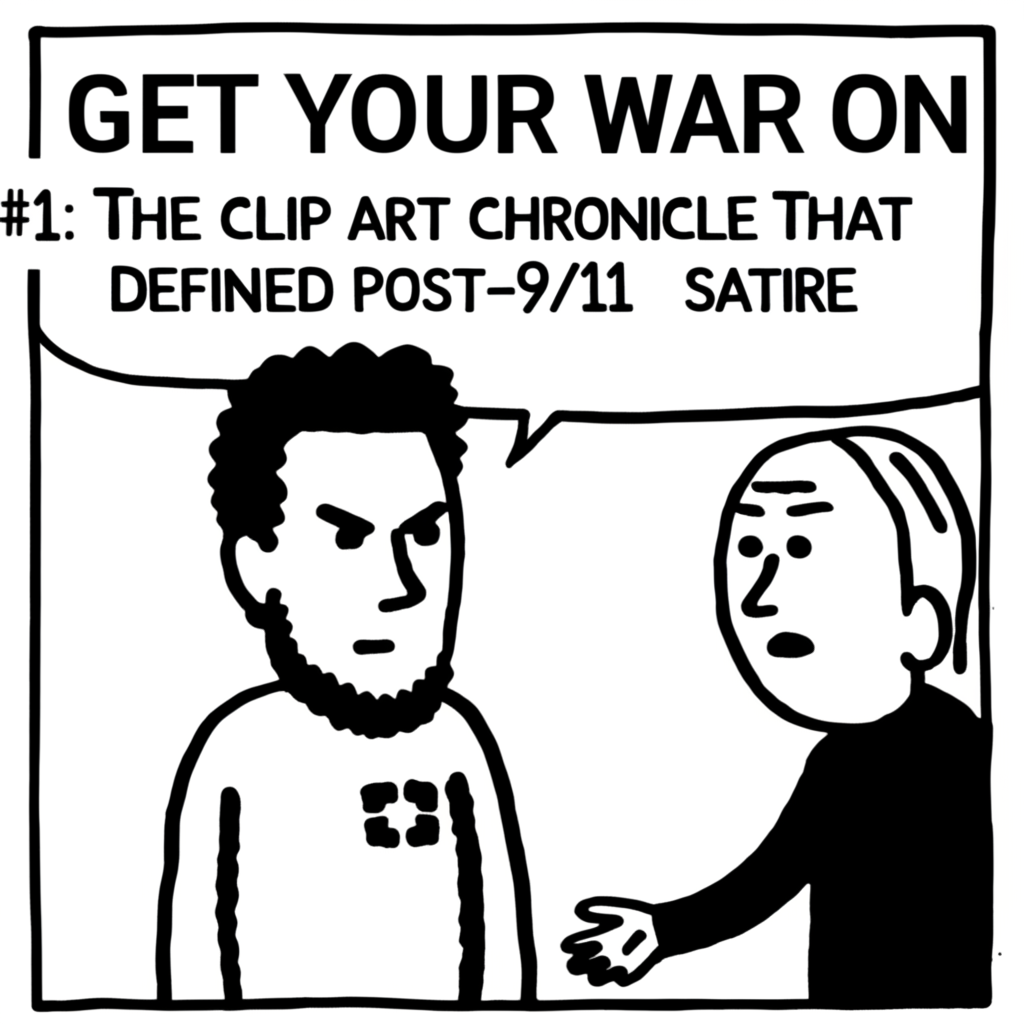

Get Your War On #1: The Clip Art Chronicle That Defined Post-9/11 Satire

The date was October 9, 2001. Less than a month had passed since the horrific attacks of September 11th had irrevocably altered the global landscape and the American psyche. The air was thick with a complex mix of grief, fear, patriotism, and a rapidly escalating sense of national purpose, quickly coalescing into what would become known as the 'War on Terror.' In this charged atmosphere, traditional media struggled to process the speed and complexity of events, often defaulting to solemn pronouncements, patriotic fervor, or punditry that felt either inadequate or overly simplistic to many.

It was into this void that a seemingly unassuming webcomic, crafted with the most basic of digital tools, emerged to offer a starkly different perspective. Titled 'Get Your War On,' its first installment appeared online on that Tuesday in October 2001. It wasn't slick, it wasn't polished, and it certainly didn't feature intricate illustrations. Instead, it presented a handful of static, generic clip art figures engaged in dialogue that was raw, cynical, anxious, and bitingly funny. This was the genesis of a cultural phenomenon, a low-fi masterpiece of political satire created by David Rees that would capture the bewildered, frustrated, and often darkly humorous zeitgeist of a nation grappling with a new kind of war.

The World in October 2001: A Nation Adrift and Mobilizing

To understand the immediate resonance of 'Get Your War On,' one must first recall the specific tenor of the times. The initial shock of 9/11 had given way to a period of intense national unity, but also profound uncertainty. The enemy was amorphous, the targets unclear, and the potential consequences vast and unknown. President George W. Bush had declared a 'War on Terror,' a phrase that itself felt unprecedented and open-ended. Military action in Afghanistan was imminent, security measures at home were rapidly increasing, and the media was saturated with images and rhetoric surrounding the conflict.

For many, particularly those who felt alienated by or skeptical of the official narrative and the wave of jingoism that followed the attacks, there was a desperate need for alternative voices. They sought commentary that acknowledged the fear and confusion, questioned the rhetoric, and offered a space for processing the absurdity that often accompanies moments of crisis. Traditional news outlets, bound by conventions of objectivity or caught up in the patriotic surge, often failed to provide this.

The internet, still a relatively young medium for mass communication and cultural production, was beginning to fill these gaps. Email chains, online forums, and early blogs became conduits for information, opinion, and creative expression that bypassed traditional gatekeepers. It was the perfect environment for something like 'Get Your War On' to not just exist, but to thrive and spread rapidly.

David Rees: The Accidental Chronicler

David Rees was not a seasoned political cartoonist with a long history of commentary. He was, at the time, known more for his earlier work, such as the zine and book series 'My New Filing Technique Is Unstoppable,' which humorously explored office culture and filing systems. This background in finding absurdity in the mundane, and presenting it with a deadpan, often surreal sensibility, proved to be surprisingly effective training for satirizing the surreal reality of the post-9/11 world.

Rees has often described the creation of 'Get Your War On' as a visceral, almost involuntary response to the events unfolding around him. He felt compelled to comment, to process, and to find a way to articulate the anxieties and frustrations that he and many others were experiencing. The tools he had readily available – a computer, basic clip art software, and an internet connection – dictated the aesthetic. This constraint, however, became the comic's greatest strength.

The Birth of GYWO #1: An Image and a Feeling

The very first 'Get Your War On' comic, published on October 9, 2001, consisted of a single panel featuring a few generic clip art figures. The image itself, often just a simple arrangement of stock characters, served as a backdrop for the dialogue. It was the text, the words exchanged between these anonymous, expressionless figures, that carried the weight of the commentary.

While the specific content of that inaugural panel might seem basic in retrospect, its power lay in its timing and its tone. It immediately cut through the noise, offering a voice that sounded like the internal monologue of many anxious citizens. It wasn't offering solutions or grand pronouncements; it was articulating confusion, questioning motives, and highlighting the inherent strangeness of the situation with a dark, gallows humor.

The use of clip art was revolutionary in its simplicity. It stripped away any pretense of artistic grandeur, making the comic feel immediate, accessible, and utterly unpolished – a direct contrast to the slick, mediated images dominating television screens. The generic nature of the figures allowed readers to project themselves or various societal archetypes onto them, making the dialogue feel universally relatable in its specific anxieties. This lo-fi aesthetic was perfectly suited for the early internet, easy to load and share, contributing significantly to its rapid dissemination.

An example panel showcasing the distinctive clip art style and dialogue of 'Get Your War On.' (Image Credit: Wired)

The Style That Defined a Movement

The signature style of 'Get Your War On' evolved slightly over time but remained fundamentally consistent: static clip art figures, often arranged in simple office or domestic settings, engaging in conversations filled with profanity, pop culture references, political jargon, and existential dread. The dialogue was the core, capturing the fragmented, overwhelming nature of information and opinion in the post-9/11 era.

Characters didn't have names; they were simply generic figures – a man in a suit, a woman at a computer, people sitting on a couch. This anonymity reinforced the idea that these were voices representing a collective anxiety or different facets of public discourse. Their bland, unchanging expressions provided a perfect deadpan counterpoint to the often frantic or cynical dialogue.

Rees masterfully used juxtaposition – placing absurdly mundane clip art figures in conversation about global politics, terrorism, and civil liberties. This created a powerful sense of cognitive dissonance, highlighting the surreal nature of living through such momentous events while still being concerned with everyday life, or the disconnect between official rhetoric and lived experience.

The humor was dark, often bordering on nihilistic, but it served as a crucial coping mechanism. In a time when expressing doubt or criticism could be perceived as unpatriotic, 'Get Your War On' offered a space for processing negative emotions and dissenting thoughts through laughter. It validated the feeling that things were chaotic, confusing, and often ridiculous, even amidst the tragedy.

Going Viral in the Early 2000s

'Get Your War On' didn't have the benefit of modern social media platforms like Twitter or Facebook for distribution. Its virality was a product of the early 2000s internet: email forwards, listservs, and links shared on personal blogs and websites. Readers who connected with the comic's perspective would save the images or the page URL and send them to friends, colleagues, and family. This organic, word-of-mouth (or rather, word-of-email) spread was incredibly effective.

The comic's format was perfectly suited for this type of distribution. Each installment was usually a single image or a short series of panels, small in file size and easy to attach to an email. The clear, concise dialogue meant the message was immediately graspable, even in a quick glance.

Within weeks of that first comic on October 9th, 'Get Your War On' had become a sensation among a certain segment of the internet-savvy population. It was discussed in online forums, referenced in emails, and eagerly awaited by a growing readership. It demonstrated the power of the internet as a platform for independent creators to reach a mass audience without needing traditional publishing or media channels.

David Rees, the creator behind the influential 'Get Your War On' webcomic. (Image Credit: TechCrunch)

As TechCrunch might have observed in a retrospective piece on early internet phenomena, the success of GYWO highlighted how compelling content, even in a low-fidelity format, could spread like wildfire through networked communities before the advent of dedicated social networking sites. It was a testament to the power of shared cultural reference points and the human need to connect over shared experiences, even difficult ones.

Themes and Evolution of the Series

While the first comic set the stage with its immediate post-9/11 anxiety, the series quickly expanded its scope to satirize various aspects of the 'War on Terror' and the broader political and cultural landscape it created. Recurring themes included:

- Media Absurdity: Critiquing the sensationalism, bias, and often nonsensical narratives presented by cable news and other media outlets.

- Political Doublespeak: Highlighting the euphemisms, jargon, and evasiveness used by politicians and officials.

- Anxiety and Fear: Giving voice to the pervasive sense of unease about future attacks, loss of civil liberties, and the unknown consequences of the war.

- Consumerism and Normalcy: Juxtaposing the gravity of the global situation with the pressure to maintain normal consumer behavior and focus on trivial matters.

- Patriotism and Dissent: Exploring the tension between national unity and the right to question government actions.

- Geopolitics: Offering cynical takes on international relations, alliances, and conflicts.

The comic evolved not in its visual style, which remained steadfastly clip art, but in the complexity and timeliness of its commentary. Rees was remarkably adept at quickly processing current events and translating them into sharp, relevant dialogue, often publishing new comics within hours or days of significant news developments. This immediacy was a key factor in its continued relevance and popularity.

'Get Your War On' and the Rise of the Political Webcomic

'Get Your War On' was not the first political cartoon on the internet, but its unique format, rapid success, and profound cultural impact made it a landmark. It demonstrated that effective political commentary online didn't need traditional artistic skill or the backing of a major media organization. All it required was a sharp perspective, a distinctive voice, and the ability to connect with an audience.

Its success paved the way for other independent online creators to explore political and social commentary through webcomics and other digital formats. It showed that a minimalist, even crude, aesthetic could be a powerful artistic choice, enhancing the message rather than detracting from it. As Wired might have noted in an article analyzing internet culture of the era, GYWO was a prime example of how the constraints of early web technology could foster new forms of creative expression and political dissent.

The comic became a touchstone for a generation that came of age online and was navigating a world reshaped by 9/11 and its aftermath. It provided a shared language and a sense of solidarity for those who felt alienated by mainstream responses to the crisis. It was discussed in workplaces, dorm rooms, and online communities, becoming a part of the daily process of trying to make sense of an increasingly confusing world.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

'Get Your War On' ran for several years, eventually concluding in 2006, though Rees has occasionally revisited the format for specific events. During its run, it was collected into several bestselling books, translated into multiple languages, and featured in exhibitions. David Rees went on to other projects, including 'Achewood' (as a guest writer), 'My New Filing Technique Is Unstoppable' books, and later, becoming a nationally recognized artisanal pencil sharpener and host of the show 'Going Deep with David Rees.'

The legacy of 'Get Your War On' is multifaceted. Firstly, it stands as a powerful, raw, and immediate artistic response to a pivotal historical moment. It captured the specific anxieties and absurdities of the post-9/11 era with an accuracy that more polished forms of media often missed.

Secondly, it is a significant artifact in the history of the internet as a platform for independent creation and political commentary. It demonstrated the power of viral content before the term was commonplace and showed that compelling voices could find an audience online regardless of traditional credentials or production values. VentureBeat, perhaps analyzing the economics of early online content, might have pointed to GYWO as an example of how minimal investment in production could yield massive cultural ROI through organic distribution.

Thirdly, it contributed to the evolution of political satire. Its blend of dark humor, existential dread, and reliance on dialogue over intricate visuals influenced subsequent online commentary and art. It proved that satire could be both deeply funny and profoundly unsettling, a necessary tool for processing difficult realities.

Even years after its conclusion, 'Get Your War On' is remembered as a defining cultural product of the early 2000s. Rereading the comics today evokes the specific feelings of that time – the fear, the confusion, the dark humor that helped people cope. The simple clip art figures and their anxious conversations remain potent symbols of a world forever changed and the struggle to understand it.

Conclusion

The first installment of 'Get Your War On' on October 9, 2001, was far more than just a simple image with some text. It was the opening salvo of a unique and vital act of cultural commentary. Born from anxiety and armed with clip art, David Rees created a series that resonated deeply because it dared to articulate the feelings many were experiencing but weren't seeing reflected in mainstream discourse. It was cynical, it was raw, and it was necessary.

In the history of internet culture and political satire, 'Get Your War On' holds a special place. It proved the power of independent voices online, the effectiveness of lo-fi aesthetics, and the enduring human need to find humor, even dark humor, in the face of uncertainty and fear. That first comic panel, simple as it was, marked the beginning of a chronicle that helped a generation get their heads around a new and frightening world.

Its legacy continues to inform how we view online commentary and the role of independent creators in shaping public discourse, proving that sometimes, the most profound statements can come from the most unexpected, and graphically simple, sources.