Say goodbye to the blue screen of death — and hello to its replacement.

The Crowdstrike disaster in July 2024 sent shockwaves through the IT world, leaving millions of Windows PCs unbootable. The incident highlighted a critical vulnerability: how could third-party security software, designed to protect systems, cause such widespread, catastrophic failure that required physical, in-person intervention from system administrators to resolve? This question became a catalyst for Microsoft, spurring the development and acceleration of initiatives aimed at fundamentally enhancing the resilience of the Windows operating system. The goal is clear: to build a version of Windows that can withstand such shocks, recover autonomously, and minimize downtime, ensuring that a single software issue cannot cripple entire fleets of computers again.

This renewed focus on robustness has coalesced into the Windows Resiliency Initiative, a broad effort that is now beginning to yield tangible results. Beyond addressing the specific vectors exposed by the CrowdStrike event, Microsoft is implementing architectural changes and new features designed to make Windows inherently more stable and capable of self-correction. These changes are not merely incremental updates; they represent a significant shift in how Windows handles critical system functions, updates, and error recovery. The ambition is to move towards a future where Windows PCs are not only more secure but also possess a built-in capacity to heal themselves, reducing the reliance on manual intervention and mitigating the impact of unforeseen software conflicts or failures.

As these initiatives mature, they promise to reshape the Windows experience for everyone, from large enterprises managing thousands of endpoints to individual users at home. The implications are far-reaching, touching upon everything from how updates are applied to how critical system errors are handled. Perhaps one of the most symbolic changes, and one that has captured significant attention, is the impending retirement of a ubiquitous and often dreaded symbol of Windows instability: the blue screen of death. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. The underlying technical shifts — in patching, recovery, security software interaction, and driver management — are far more profound and hold the key to a genuinely more resilient Windows ecosystem.

With that in mind, let’s delve into the specifics of what Microsoft has been building and what users can expect from Windows 11 PCs in the near future and beyond. These changes, often operating silently in the background, are set to make Windows more dependable than ever before.

The Advent of Hotpatching: Seamless Updates Without the Reboot

For decades, a fundamental part of the Windows experience has been the mandatory reboot following system updates. While Windows has become more sophisticated in allowing updates to be downloaded and partially installed in the background, critical security fixes often required a system restart to take full effect. This created a window of vulnerability, as users might delay reboots for convenience, leaving their systems exposed to threats that the downloaded patches were meant to address. Hotpatching represents a significant departure from this model, promising to revolutionize how updates are applied and perceived.

Hotpatching, a concept previously more common in server environments and specialized systems requiring high uptime, allows Windows to apply security updates directly into the running memory of the operating system without requiring a full system restart. This means that once a security patch is downloaded and installed, its protective measures are immediately active. The difference is subtle but crucial: previously, installation was separate from application, with the latter dependent on a reboot. With hotpatching, installation *is* application for many critical fixes.

While the current implementation of hotpatching is primarily targeted at enterprise users leveraging the “Windows Autopatch” cloud service on Windows 11 Enterprise, its potential implications for the broader Windows user base are immense. Microsoft's blog posts on the subject, while focusing on the enterprise benefits of reduced downtime and simplified patch management for IT departments, hint at the underlying technology's potential for wider adoption. Imagine a future version of Windows — perhaps Windows 12 or a subsequent update to Windows 11 — where the need to reboot for monthly security updates becomes a relic of the past. While major feature updates might still necessitate a restart, the frequent, disruptive reboots for security patches could be largely eliminated.

This shift would not only enhance security by ensuring patches are applied promptly but also significantly improve the user experience. No more interruptions during critical work sessions, no more delayed protection because a reboot was inconvenient. The technology is complex, involving sophisticated memory management and code injection techniques to swap out vulnerable code with patched versions on the fly. However, the user-facing result is elegantly simple: updates happen, and the system remains running. As Microsoft refines this technology within the enterprise space, the prospect of bringing this seamless updating capability to consumer versions of Windows becomes increasingly plausible, marking a major step towards a more resilient and less intrusive operating system.

The Self-Healing PC: Quick Machine Recovery Gets Smarter

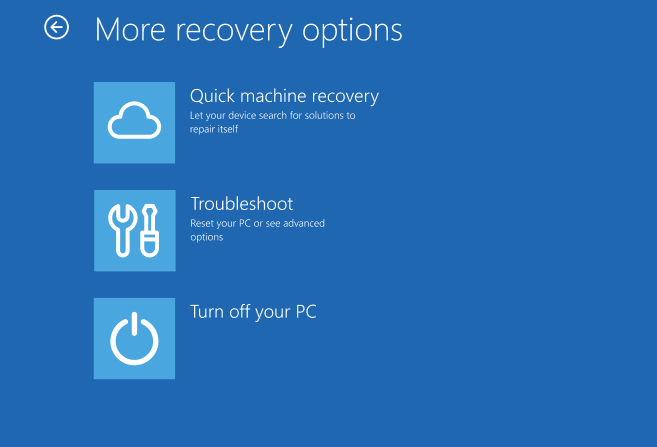

When a Windows PC encounters a critical error that prevents it from booting normally, it typically enters the Windows Recovery Environment (WinRE). This environment provides tools for troubleshooting and repairing common startup issues. However, as demonstrated by the CrowdStrike incident, there are scenarios where WinRE itself might not have the necessary information or fixes readily available to resolve complex problems, especially those caused by third-party software interacting deeply with the system.

Quick Machine Recovery (QMR) is Microsoft's answer to this limitation, designed to transform WinRE into a more proactive, self-healing system. The core idea behind QMR is to enable the recovery environment to connect to the internet and download specific fixes directly from Microsoft's servers when it encounters a problem it cannot solve locally. This is a significant upgrade to WinRE's capabilities, leveraging network access that has technically existed for years but was not previously utilized for automated problem resolution in this manner.

Consider a scenario similar to the CrowdStrike outage: a buggy driver, a problematic Windows update, or faulty security software renders the main Windows installation unbootable. In the past, resolving this might have required manual steps, potentially involving creating bootable media or applying fixes offline. With QMR, when the PC enters the recovery environment, it can establish a network connection (via Wi-Fi or wired Ethernet) and query Microsoft's servers for known solutions to the specific issue causing the boot failure. If Microsoft has identified a widespread problem and developed a fix, QMR can download and apply it automatically, potentially restoring the system to a working state without requiring user intervention beyond the initial boot into recovery.

This capability is particularly valuable in enterprise settings, where IT administrators can leverage QMR to remotely diagnose and repair issues across numerous machines without needing physical access to each one. Microsoft is making QMR available to both Windows 11 Professional and Enterprise users, where it can be managed via tools like Intune, and critically, it is enabled by default on Windows 11 Home. This means average users, who might lack the technical expertise to navigate complex recovery scenarios, will benefit from an operating system that is better equipped to fix itself silently in the background. QMR is expected to roll out later in the summer, promising a significant reduction in the impact of boot-blocking errors and a more resilient Windows startup experience.

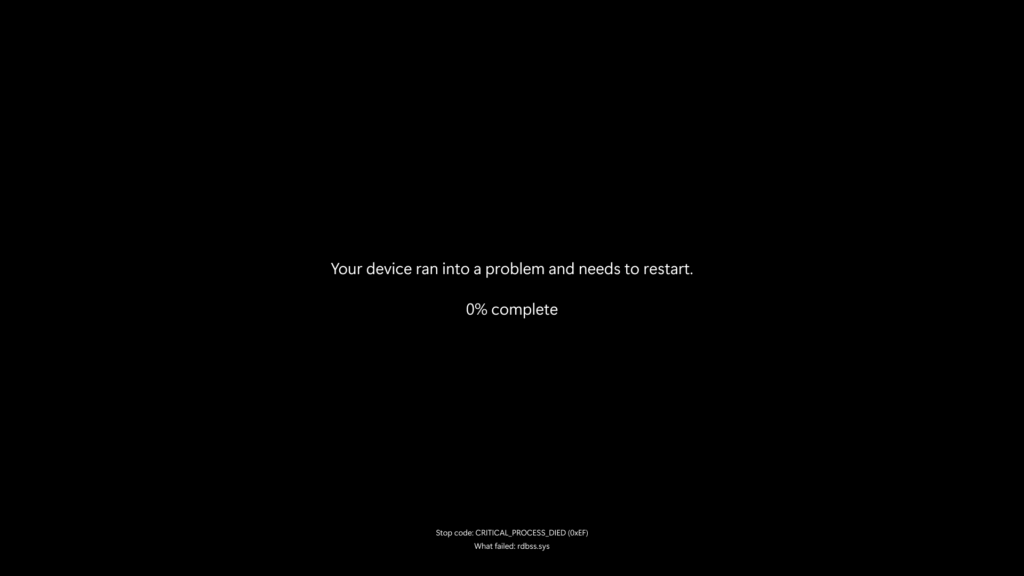

The End of an Era: The Black Screen of Death Arrives

For generations of Windows users, the blue screen of death (BSOD) has been the unmistakable, often dreaded, symbol of a critical system failure. It's an icon of instability, a moment of abrupt interruption accompanied by technical jargon and, in later versions, a frowny face and a QR code. While the underlying causes of these critical errors haven't vanished, Microsoft is making a highly visible change: the blue screen is being replaced by a black one. This isn't just a cosmetic tweak; it's part of a broader effort to streamline the error reporting interface and potentially integrate better with modern display technologies.

The new black screen of death retains the essential information needed for troubleshooting — primarily the stop code and a brief explanation of the error. It discards the more user-friendly but often unused elements like the large frowny face and the scannable QR code introduced with Windows 8. Microsoft's rationale is that this simplified interface provides the critical technical details needed by support personnel or advanced users, making remote troubleshooting easier by presenting the core information without visual clutter.

More significantly, the context surrounding these critical errors is changing. With improvements like Quick Machine Recovery, the system is better equipped to potentially resolve the issue automatically upon restart. Furthermore, Microsoft has focused on drastically speeding up the crash dump collection process in the Windows 11 24H2 update. This process, which captures vital diagnostic information when a system crashes, now reportedly takes around two seconds. This rapid data collection, combined with faster reboot times, means the period of disruption caused by a critical error is significantly reduced. In this accelerated recovery scenario, the need to manually scan a QR code with a phone feels increasingly outdated. While the sight of a full-screen error message is never welcome, the transition to a black screen, coupled with faster recovery mechanisms, is part of the broader push for a more streamlined and resilient Windows experience.

Architectural Shift: User-Mode Antivirus for Enhanced Stability

One of the most critical takeaways from the CrowdStrike incident was the inherent risk of security software operating deep within the Windows kernel. The kernel is the core of the operating system, with privileged access to all hardware and software resources. While this level of access is necessary for security software to effectively monitor and protect the system, it also means that a malfunction or bug in the security software can have catastrophic consequences, potentially crashing the entire operating system, as seen in July 2024.

This isn't a new problem. Nearly two decades ago, during the development of Windows Vista, Microsoft explored the idea of moving security software out of the kernel. However, facing pressure and concerns about anti-competitive practices from third-party security vendors — particularly as Microsoft was developing its own antivirus solution — the company ultimately allowed security software to retain its deep kernel integration, albeit with some tightening of kernel access controls compared to previous Windows versions. This historical decision, influenced by past antitrust challenges related to bundling software like Internet Explorer, left a fundamental architectural vulnerability in place.

The CrowdStrike disaster served as a stark and undeniable demonstration of the risks associated with this architecture. It provided Microsoft with renewed impetus to revisit the idea of shifting security software to a less privileged execution mode. The result is the “Windows endpoint security platform,” an initiative aimed at enabling antivirus and other endpoint protection software to run outside the Windows kernel, in user mode. In user mode, software has restricted access to system resources and memory. If a user-mode process crashes, it typically doesn't bring down the entire operating system; instead, the operating system can terminate the faulty process and continue running.

This architectural change is profound. It means that a bug in an antivirus program, while still potentially disruptive to the security software itself, should no longer have the ability to cause a system-wide crash or render the PC unbootable. The operating system kernel remains protected, isolated from potential instability introduced by third-party security agents. Microsoft is launching a private preview of this new platform for its antivirus partners, allowing companies like Bitdefender, Sophos, Trend Micro, and even CrowdStrike itself to begin developing versions of their software that can leverage this user-mode execution capability.

As noted in a Microsoft blog post, these security partners have expressed enthusiasm for the initiative, recognizing the potential for increased stability and reliability. Microsoft is navigating this transition carefully, likely mindful of the historical antitrust concerns, by collaborating openly with a wide range of security vendors. While this user-mode antivirus platform is not yet ready for widespread consumer use, its development represents a critical step towards a more fundamentally resilient Windows architecture, addressing a long-standing vulnerability that was dramatically exposed by the CrowdStrike incident. It's a necessary evolution, even if it means some security software might need to adapt its approach to operate effectively within the new constraints.

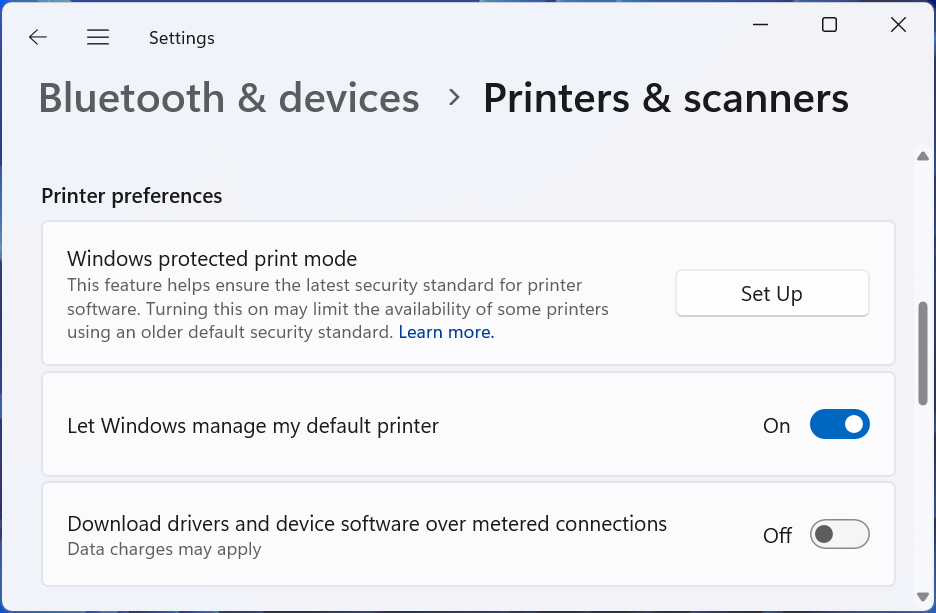

Cleaning Up the Kernel: Protected Print Mode and Driver Management

Beyond security software, another common source of kernel-level instability has historically been hardware drivers. Drivers are essential pieces of software that allow the operating system to communicate with hardware devices. Because they often require low-level access to function correctly, many drivers run in kernel mode. A poorly written or buggy driver can easily cause system crashes, including the dreaded BSOD.

Over the years, Microsoft has made significant strides in standardizing drivers for common peripherals like USB devices, making them plug-and-play. However, certain device categories, most notably printers, have lagged behind. Printer drivers have been a particularly frequent source of both stability issues and security vulnerabilities, often requiring complex, proprietary software suites that integrate deeply with the system.

Microsoft is now actively working to modernize and standardize the printer driver ecosystem, moving towards a model where printers utilize a more universal, secure driver architecture. This effort involves a migration to the “Windows modern print stack,” which aims to reduce the need for complex, kernel-mode drivers provided by printer manufacturers.

As part of this transition, Windows 11 includes a feature called Windows Protected Print mode. While not enabled by default yet, users can activate it in Settings (Settings > Bluetooth & devices > Printers & scanners). When enabled, Protected Print mode prevents the installation of older, legacy third-party printer drivers and enforces the use of the modern print stack, primarily supporting Mopria-certified printers. This shift moves printer functionality towards a more standardized, potentially less privileged execution model, reducing the attack surface and the risk of kernel-mode crashes caused by faulty printer drivers.

Complementing this, Microsoft is also undertaking a cleanup effort on Windows Update, removing older, unwanted legacy drivers from being automatically offered to users. While these drivers might still be available for manual installation if absolutely necessary for older hardware, Windows Update will prioritize providing modern, standardized drivers. This proactive management of the driver ecosystem, although not officially part of the Windows Resiliency Initiative, aligns perfectly with its goals by reducing the potential for instability and security risks introduced by outdated or poorly designed kernel-mode drivers. These seemingly minor changes contribute to the overall health and reliability of the Windows kernel, making the entire operating system more robust.

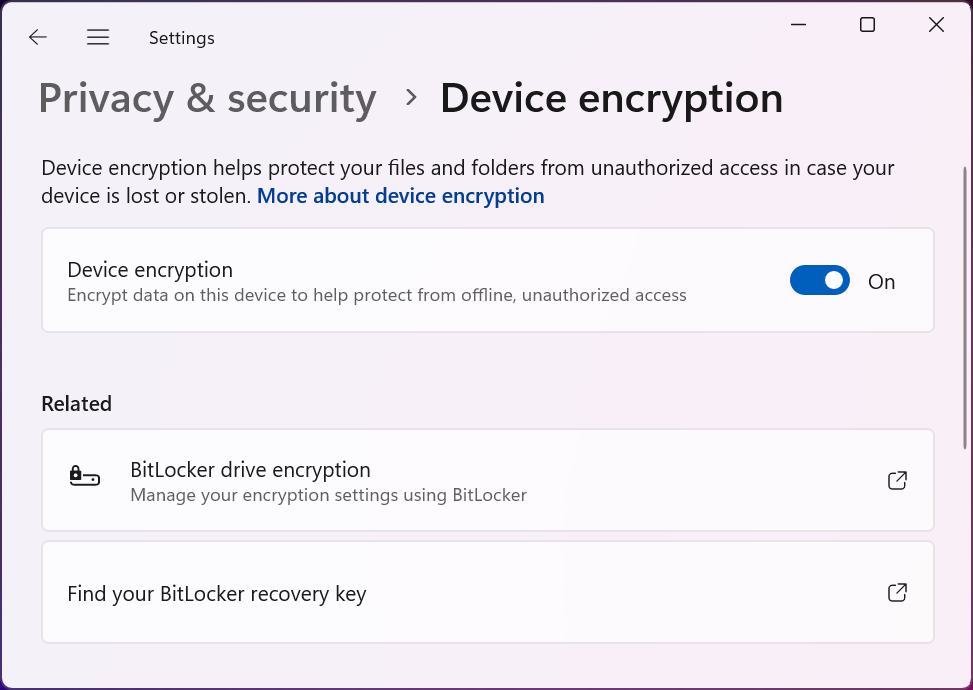

Enhanced Data Security: Encryption by Default Becomes More Common

While not directly related to system crashes or boot failures, data security is a critical component of overall system resilience. If a device is lost or stolen, the ability to protect the data stored on it is paramount. Disk encryption is the primary mechanism for this protection, rendering the data unreadable to anyone who doesn't have the decryption key.

Historically, Microsoft's approach to disk encryption on Windows has been somewhat fragmented. Full BitLocker drive encryption, offering comprehensive protection, was primarily available on Professional and Enterprise editions of Windows. Home editions had access to a simplified feature called BitLocker device encryption, but its availability was often dependent on specific hardware configurations and OEM implementations, leading to inconsistency.

Recognizing the importance of data protection for all users, Microsoft has been working to make encryption more widely available and consistently enabled. With the Windows 11 24H2 update, Microsoft lowered the hardware requirements for BitLocker device encryption and expanded the scenarios where it is automatically enabled by default on new installations. This means a greater number of new Windows 11 PCs, including those running Home editions, will have their storage encrypted out-of-the-box.

For this default encryption to work seamlessly, especially for Home users who might not be familiar with encryption keys, Windows automatically backs up the BitLocker recovery key to the user's Microsoft account. This provides a crucial safety net, allowing users to recover their data if they forget their login password or encounter issues accessing their encrypted drive. While this feature requires signing in with a Microsoft account to enable the key backup, it significantly increases the likelihood that user data will be protected against physical theft or unauthorized access.

While Microsoft doesn't prominently advertise whether a PC's storage is encrypted — users typically need to check in Settings or Control Panel — the push towards enabling it by default on more hardware configurations is a significant step forward for data security. It adds another layer of resilience, protecting sensitive information even when the physical device is compromised. This quiet but crucial improvement complements the system-level resiliency features by safeguarding the data that the operating system manages.

A More Robust Future for Windows

In the modern computing landscape, where systems are constantly connected and exposed to a myriad of potential issues — from software bugs and driver conflicts to malicious attacks and unexpected hardware failures — the ability of an operating system to remain stable, recover quickly, and protect data is paramount. The CrowdStrike incident served as a powerful reminder that even seemingly minor software updates can have cascading, catastrophic effects if the underlying architecture is not sufficiently robust.

Microsoft's response, embodied in the Windows Resiliency Initiative and related efforts, demonstrates a renewed commitment to building a more dependable operating system. Features like hotpatching promise to reduce disruptive downtime and ensure timely application of security fixes. Quick Machine Recovery empowers the system to heal itself from critical boot errors by leveraging cloud-based solutions. The architectural shift towards user-mode antivirus aims to prevent third-party security software from crashing the kernel. Improvements in driver management, particularly for printers, reduce another historical source of instability. And the expansion of default disk encryption enhances data security, adding another layer of protection to the overall system.

These under-the-hood improvements, while perhaps less flashy than new AI features on Copilot+ PCs or user interface redesigns, are arguably far more critical to the long-term health and trustworthiness of the Windows platform. They address fundamental vulnerabilities and pain points that have affected users and IT professionals for years. By focusing on stability, automated recovery, and secure architecture, Microsoft is building a foundation for a more reliable computing experience.

The transition away from the iconic blue screen of death, while symbolic, highlights this broader shift. The goal is not just to change the color of the error screen, but to make such screens a far rarer occurrence, and when they do appear, to ensure the system can recover faster and more effectively. For both large organizations managing complex IT environments and individual users relying on their PCs for daily tasks, these advancements in Windows resiliency are genuinely good news, promising a more stable, secure, and ultimately, a more user-friendly future.

The path to perfect stability is long and complex, but the steps Microsoft is taking — driven by lessons learned from past incidents — indicate a clear direction towards a more robust Windows ecosystem. It's encouraging to see this focus on the core reliability and security of the operating system, ensuring that the platform can better withstand the inevitable challenges of the digital world.